One of the oldest buildings in London, the Tower of London is staffed by Yeoman Warders who are known colloquially as “Beefeaters.” The two go together like beans on toast and have been since the Tudor Period. Today, the Tower of London is more a tourist attraction than a fortress, and the Beefeaters serve more as tour guides and caretakers than guards. To understand more about the history and qualities of both, we’re going to do a brief dive into the relationship between them and how it has evolved over the centuries.

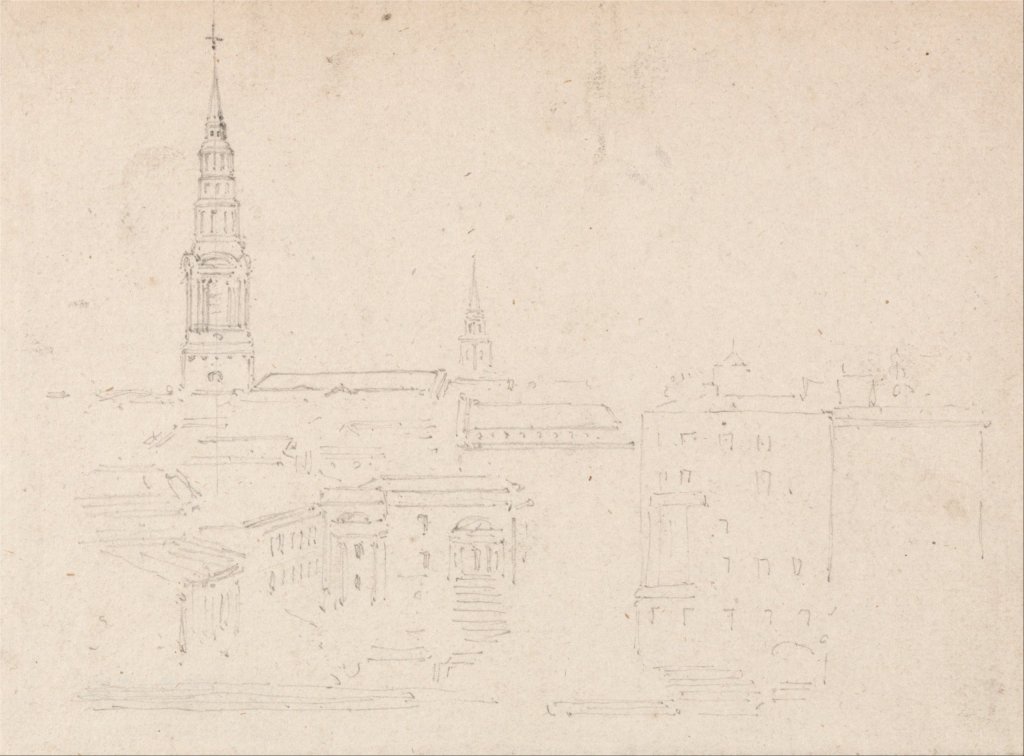

The Tower of London was one of the first buildings constructed after King William I’s conquest in 1066. He began on it shortly after being crowned in order to hold the City of London in his control and quickly send military aid to surrounding counties in case of rebellion. The White Tower was completed in 1093 under William’s son, King William II. The Innermost Ward and the Inner Wards were begun under King Richard I and completed under King Henry III, bringing the Tower of London into a more fashionable royal residence for the 13th Century. The final Outer Ward was then built during the reign of King Edward I. Over time; the tower became less of a residence for the Sovereign and more likely to have “permanent” guests who were prisoners of the Crown. The most famous of these prior to the Tudor Era were the “Princes in the Tower,” King Edward V and his brother Richard, Duke of York, who were imprisoned by their uncle King Richard III and then mysteriously disappeared.

It was under the reign of King Henry VII that the Tower of London began to serve more as a prison and a royal armory than a home. It was also during his reign that Henry formed the Yeoman Warders in 1485 as his personal bodyguards. The Warders got the nickname “Beefeaters” as they were the only ones permitted to eat beef from the King’s table, though another account by Cosimo III de Medici in 1669 is suggested to be the origin of the name for his account of how the Yeomen were permitted a ration of beef a day. These elite bodyguards traveled with Henry everywhere, but Henry felt that a contingent of them should also guard the Tower of London, beginning their long association with the fortress. Yeoman Warders were eventually granted their “undress” uniform which features a dark blue color with red accents and the Royal Cypher at its center.

The Yeoman Warders eventually became the permanent garrison of the Tower of London with the ability to draw recruits from nearby Tower Hamlets if needed for the Tower’s defense. Over the centuries, their duties trended less toward guarding the Sovereign (a job that was turned over to the Yeomen of the Guard), and they guarded the Tower, including the prisoners, armory, and the Crown Jewels. Today, the Beefeaters serve primarily as greeters and tour guides at the Tower of London. One Yeoman Warder also serves as the Tower’s Ravenmaster, looking after the famous birds that inhabit the grounds, a position currently held by retired Staff Sergeant Christopher Skaife. Perhaps the most important responsibility of the Yeoman Warders is the Ceremony of the Keys, in which the keys for the Tower are presented every night before the Tower of London is closed to visitors.

All Yeoman Warders are retired military and live with their families in accommodations within the Tower, though many also have homes away from the Tower and are required to have an outside home when they retire. The Beefeaters also have their own private pub within the Tower, the Yeoman Warders Club, for their members and invited guests. For centuries Yeoman Warders could only be members of the British Army, Royal Marines, and Royal Air Force, and sailors of the Royal Navy were excluded because they pledged their loyalty to the Admiralty rather than the monarch. This changed due to a petition from the Governor of the Tower to Queen Elizabeth II in 2009. The Beefeaters had also been all men until they were joined by Moira Cameron in 2007. Even though the Beefeaters no longer serve their original purpose, their importance to, and history with, the Tower of London means that the two will be tied together for a very long time.