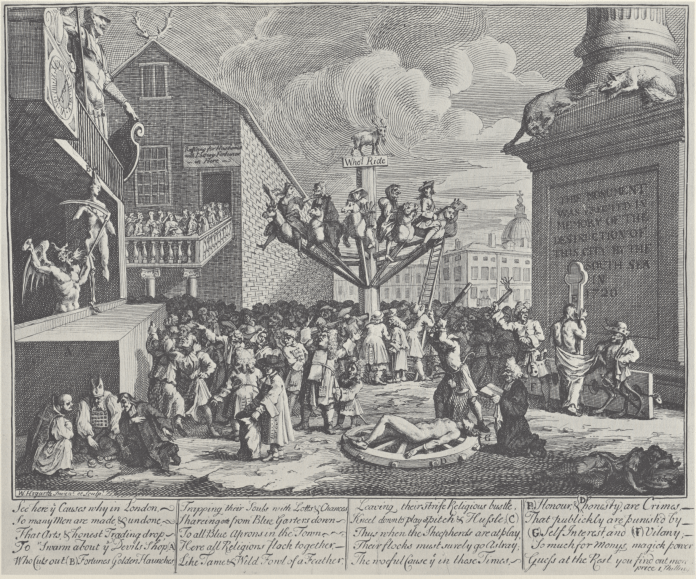

While using images to tell a story dates back to cave paintings and later on to the Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, and other cultures, political cartoons or comics as we know them are a tool of satire that’s only a few hundred years old. While the art of cartooning and caricature began in Renaissance Italy, historically, the use of pictorial satire began with William Hogarth in the early 18th Century. In his work, Emblematical Print on the South Sea Scheme, the artist sought to criticize the greed and corruption of the South Sea Company, using real and allegorical persons and places. The print inspired a host of imitators on the Continent and is credited as a precursor to later political cartoons of the era, if not the first.

The medium grew in popularity over the next few decades, with the works of Hogarth and George Townshend often shared as after-dinner entertainment and enjoyed by the lower classes who would view them outside of London’s print shops. While Hogarth was more moralizing in his themes, Townshend was overtly political. The pictorial nature of these early satirical cartoons also lent itself to be easily understood by the illiterate, easily conveying the subject matter and meaning to a wide audience.

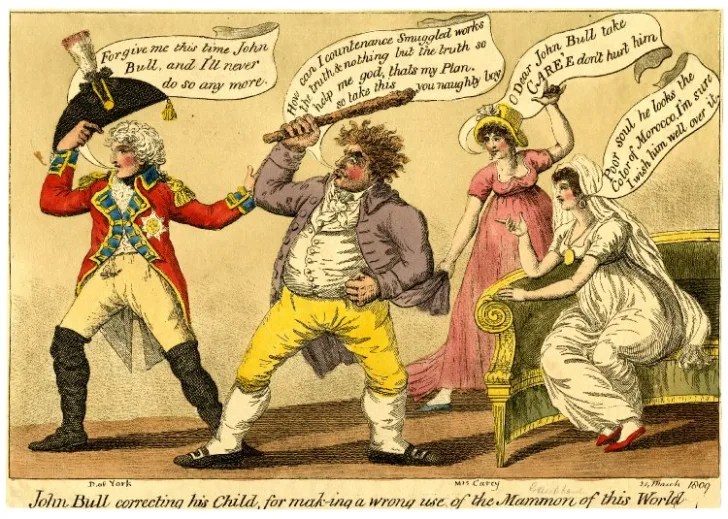

Towards the end of the 18th Century, the two primary artists of the genre were James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson. Gillray is sometimes described as “the father of the political cartoon.” He particularly enjoyed lampooning the government and especially King George III, whom he thought of as a fool. While initially supportive of the French Revolution, Gillray’s works turned on the French as the revolution descended into the violence and chaos of the Reign of Terror. He also turned his attention to Napoleon, and a cartoon from 1805 showed the competing global interests of England and France as the French Emperor and Prime Minister William Pitt are depicted carving up the world like a Christmas pudding.

Interestingly, despite the Crown and the government still having a significant influence on publishing in the United Kingdom, the cartoons were taken in good nature. Officials were far more likely to buy up all editions of a satirical cartoon or bribe the publishers to prevent people from seeing them rather than taking action against the cartoonist. What was depicted was often a lot raunchier than what we might see today, and important persons could be depicted vomiting, urinating, or even defecating in the cartoons. One particularly famous work from 1740 satirized Prime Minister Robert Wapole’s love of patronage by having a giant caricature of Wapole in front of the British Treasury, presenting his bare bottom to be kissed before people were allowed to enter.

By the 19th Century, cartoonist magazines such as Punch and political newspapers regularly published political cartoons. As per the norm for caricatures, often one attribute of the subject was overexaggerating to help identify them. Pitt the Younger was often depicted as drunk, Churchill was rarely drawn without one of his trademark cigars, Thatcher was either shown with a handbag or her nose greatly enlarged, and John Major was often depicted wearing his underpants outside of his clothes after Labour spin master Alastair Campbell suggested he tucked his shirt into them.

Today, the importance of political cartoons to free speech and holding officials to account for their actions continues. The history and cultural significance of these works can be found in art museums across the United Kingdom, but most pointedly at The Cartoon Museum in London. With its large collection, The Cartoon Museum features political cartoons heavily in its exhibits, along with non-political humor comic strips, superheroes, and more. It’s highly recommended to visit the next time you’re in London to understand more about one the most important genres of free expression and criticism.