St Bride’s Church on Fleet Street is a Christopher Wren church built after the Great Fire of London. It’s the journalists’ church, and the spire is the original inspiration for tiered wedding cakes. It is a City of London working parish church and welcomes visitors as a heritage attraction too.

NOT THE FIRST

This wasn’t the first church at this location or even the second. It’s the eighth!

ROMAN

The history goes back 2000 years as there may have been a Roman villa here that was used as a place of Christian Worship which could be why St Brigid, or her followers, founded a church here in the fifth century.

The crypt has a small museum, but you also see the remains of a Roman pavement dating back to around AD 180 and a range of Roman artifacts that were discovered on this site.

MEDIEVAL

The first stone church was built here in the sixth century and survived for three centuries. The next building lasted until 1135 and was followed by its twelfth-century successor which had an impressive tower from which rang one of London’s four curfew bells.

Between the 11th and 13th centuries, the population of London increased significantly, from less than 15,000 to over 80,000. By the year 1200, the capital city was, in effect, Westminster, a small town upriver from the City of London, where the Royal Treasury was located, and financial records were stored.

St Bride’s was a significant building between the City of London and Westminster. In 1205, the Curia Regis, a council of landowners and ecclesiastics (in effect, a predecessor of today’s Parliament, charged with providing legislative advice to King John), was held in St Bride’s. And in 1207, King John held his Parliament at the church.

The wealthy bequeathed money to pay priests to pray for their souls. The less wealthy joined parish guilds which provided similar benefits. The Guild of St Bride was confirmed by Edward III in 1375, and 100 of its members still serve the church.

The crypt has on display the remains of the churches that stood on this site between the 11th and 15th centuries and examples of medieval floor tiles, roof tiles, stonework, glass, and other artifacts from the period. The Eagle Lectern that is still in use was rescued from the medieval church.

PRINTING

In 1476, William Caxton, a merchant, businessman, and diplomat, brought to this country for the first time a printing press that used moveable type. He set it up on a site adjacent to Westminster Abbey. It is said that modern advertising began when Caxton wanted to sell a service book and produced a memorable poster.

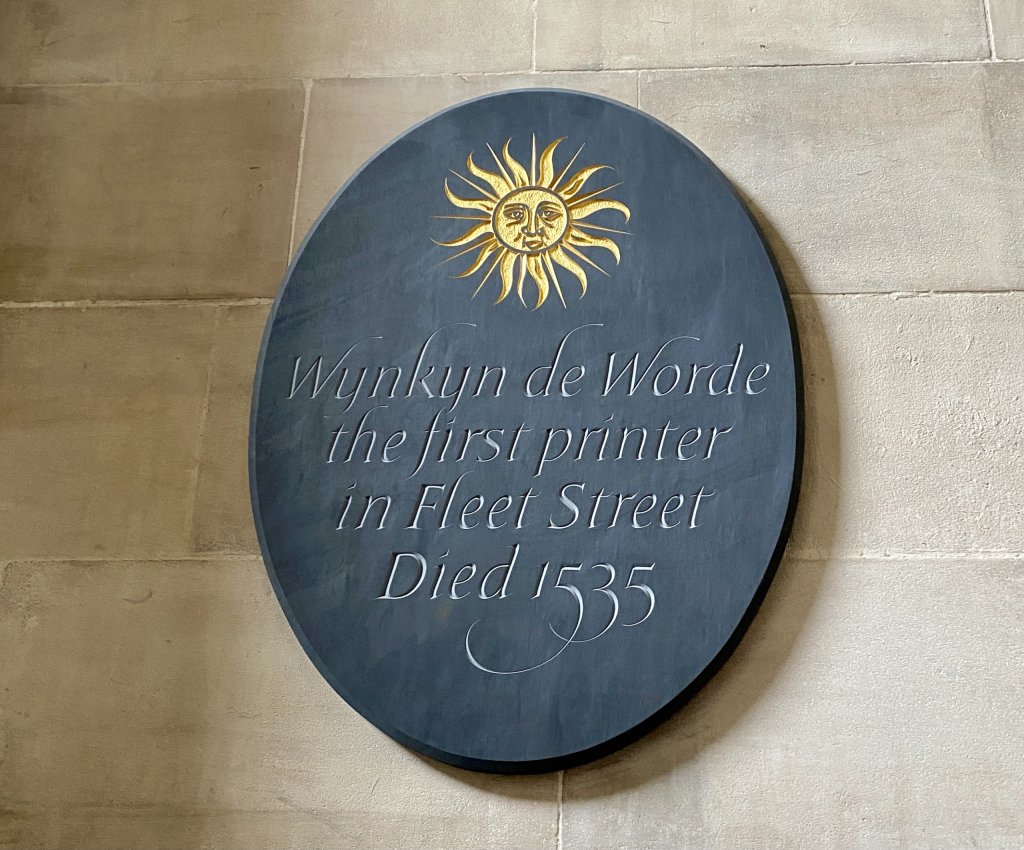

After Caxton’s death around the year 1492, his press was acquired by his apprentice, the printer Wynkyn de Worde, who was dependent upon printing for his livelihood and needed to ensure its commercial viability.

At the time, the area around St Bride’s had become a haven for clergy, who were unable to afford the high cost of living in the very heart of the medieval city. Since the clergy possessed almost a monopoly of literacy in those days, alongside the lawyers who were also based in the area, they were the printers’ best customers. So Wynkyn de Worde followed the best commercial principles and moved his business to the customer base, setting up his printing press in the churchyard of St Bride’s in 1500.

Wynkyn de Worde was buried at St Bride’s in 1535, and a plaque commemorating his life can be seen in the church. St Bride’s is also proud to possess an original example of Wynkyn de Worde’s printing, dating from 1495.

GREAT PLAGUE

During the Great Plague of 1665, the Court of Charles II plus lawyers, merchants, doctors, and many clergy fled the city in fear. But the poor had to stay, and 2,111 people died in St Bride’s parish (100,000 Londoners lost their lives – 20% of its population). The vicar of St Bride’s, Richard Peirson, chose to remain. At the height of the plague in September 1665, Peirson buried 636 people within a month – 43 of them on a single day. The dead included two of his Churchwardens.

Remarkably, Peirson survived the plague, and he was succeeded as vicar in August 1666 by Paul Boston. Literally, two weeks later, another landmark disaster occurred.

GREAT FIRE OF LONDON

On 2 September 1666, fire broke out in the bakery of Thomas Farriner in Pudding Lane. Fanned by strong winds from the east, the fire spread rapidly. On 4 September 1666, the fire crossed the Fleet River (which today runs underground) and engulfed St Bride’s. All that could be saved from the fire was some fused bell metal – some of which can be seen in the crypt.

Vicar Paul Boston left £50 in his Will to the church, which purchased new communion vessels that are still in use today.

SIR CHRISTOPHER WREN

The Great Fire of London destroyed 87 churches. Despite Wren’s conviction that only 39 were necessary to serve such a small area, St Bride’s was among the 51 to be rebuilt.

The £500 required as a deposit by Guildhall to launch the project was raised in a single month: a remarkable effort, given that most of the parishioners had lost homes and businesses in the disaster.

Joshua Marshall, the King’s Mason, was the main contractor. He was a parishioner and also worked with Wren on the Temple Bar and the Monument. One of his assistants was the young Nicholas Hawksmoor, who was to become a renowned architect himself.

Construction started in 1671 and progressed quickly as Wren had built a hostel for the workmen nearby on Fleet Street. The Old Bell Tavern is still there.

Built from Portland stone, the church cost, apart from the steeple, £11,430, making it the third most expensive of all of Wren’s churches. Wren built over the remains of the previous six churches, thus forming extensive crypts.

By 1674 the main structural work was complete, and a year later, the church finally reopened for worship on Sunday 19 December 1675. St Bride’s was one of the first post-fire churches ready for worship. And Fleet Street was one of the first main roads to be substantially restored.

Shortly after opening, galleries were added along the sides of the west walls.

WEDDING CAKE SPIRE

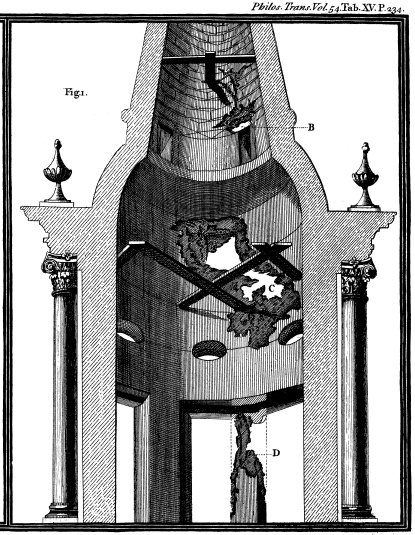

A model of Wren’s original plan for the steeple can be seen on the font inside the church. (The font is from St Helen’s, Bishopsgate.) It was a much shorter cupola design without the additional tiers. In the end, the 234 ft steeple – Wren’s tallest – was completed in 1703.

It was struck by lightning in 1764 and lost 8 feet of height, bringing it down to 226 ft. George III was upset about this, and one of the people he called upon to advise him was Benjamin Franklin. Unfortunately, Franklin and the monarch did not agree. The king insisted the new lightning conductor should have blunt ends, while Franklin thought pointed ends were more effective. This led to political pamphleteering about ‘good blunt, honest King George’ and ‘those sharp-witted colonists.’ It can’t have helped having two leading figures showing public political tempers so close to American Independence.

William Rich was an apprentice to a baker near Ludgate Circus. He fell in love with his master’s daughter. When he set up his own business at the end of his apprenticeship, he won her father’s approval for her hand in marriage. Rich wanted to create a spectacular cake for the wedding feast and took inspiration from the spire of St Bride’s church. He created a cake in layers and began the tradition of the tiered wedding cake. Until his death in 1811, he made a small fortune peddling cakes under its design. Both William and Susannah are buried at St Bride’s.